Short Story :: Anukrti Upadhyay

I walked sideways through the narrow aisle between the seat-banks. At my age, I have no shame in confessing that I am built generously. I used to be big even as a little girl, not embarrassingly so, just on the large side. Now some parts of my body hang or sag and hinder me when I am doing chores or boarding a train or making love, but I can manage. Over five decades of wear and tear in the process called life, with three children, borne, bred and worried into shape, is bound to leave marks, some visible, some not. In any case, airplane aisles are not built for bodies with experience, only for waifs in skirts and at times the waifs struggle too, pressed in corners to let people in urgent need of toilets pass, dodging elbows, knees and feet sticking out of the seat-rows.

Over five decades of wear and tear in the process called life, with three children, borne, bred and worried into shape, is bound to leave marks, some visible, some not.

What I am trying to say is that I am used to both my bulk and the narrowness of a plane’s aisle and it was the little man in the dirt–brown shirt who was at fault for what happened. I had had my eye on him since the queue at the check-in counter. He had tried to sidle ahead of others there too just as he was trying to squeeze past me in the narrow aisle. Maneuvering so that I could give him a look was difficult but I managed. There is too little discipline these days and it shows everywhere. Everyone’s given too much freedom, too much of that ‘let them discover for themselves’ kind of nonsense around. I should know, I teach Physical Education at an all-girls’ school and the things they can get away with these days, from shorts to answering back, would appal anyone. Anyway, I am digressing. I located my seat, an aisle one in a two-seat row. A young woman, in the palest of sandalwood-yellow saree, was in the window seat. I picked up my stroller, I had chosen it carefully to ensure it met cabin-luggage specifications and thus avoid long waits at luggage carousels and the uncertainty of whether it will arrive. Not that I have lost anything, the baggage inevitably finds one.

Anyway, I grasped my stroller with both hands and lifted it. Even my children, critical as they are about almost where I am concerned, admire my strength and admit that at least some of the weight I carry around is muscle. Please don’t think I am boasting, I just want it to be completely clear that but for that little weasely man, I would have easily placed my stroller in the overhead compartment, fitted my bulk into the seat and slept my way through to my destination. Instead, this is what happened – just when I needed my balance most, the puny creature shoved me from behind. Everything happened rather quickly – the poke in my back, me swaying dangerously with the stroller up-raised and somehow managing to push it into the overhead compartment and in the process dealing a swinging blow to the young woman in the window seat with the somewhat large leather hand bag hanging from my shoulder.

Under the unbroken skin, blood-vessels had oozed but she did not as much as grimace with pain. I admire that kind of fortitude. I was taught to not make a single sound even if I were being torn apart by pain.

My eldest, a twenty five year old young woman now and forthright to a fault, has spoken many times about this bag of mine. She considers it offensive to aesthetic sense, pointing out that it highlights my bulk. She is yet to learn that at a point in life, utility triumphs over beauty. However, even she, in her frequent and lengthy criticism of the bag, had not considered its potential to cause injury. It’s tough, double-seamed, stiff edges were formidable and a red welt was already forming on the young woman’s arm. I immediately began apologizing. “I am so sorry, this looks so painful… I have some excellent balm…” I rummaged in the guilty bag and produced my aloe vera balm. The young woman turned to me. She wasn’t beautiful, her eyes were too deep-set, the cupid’s-bow mouth too heavy, yet when she turned her slender neck and cast her large eyes at me, I felt her attraction. “I am sorry…” I repeated, “I…it was an accident.” I glared briefly at the man in the dirt-brown shirt. He was still clumsily trying to lift his own case and staggering under its weight. “I also have some Arnica…it is an excellent pain-reliever.” She followed my eyes and looked at her arm where the welt had turned an angry red. Under the unbroken skin, blood-vessels had oozed but she did not as much as grimace with pain. I admire that kind of fortitude. I was taught to not make a single sound even if I were being torn apart by pain. I carefully slid into my seat next to her. “You must apply some balm; your arm will be very stiff and painful soon.”

“Don’t worry, it does not hurt.”

This was carrying physical endurance to extreme. I knew that her shoulder and arm must be throbbing by now. “Here, let me apply it for you.” I unscrewed the top of the bottle, “You are like my daughter. I can’t tell you how terrible I feel.” She silently allowed me to rub the balm in, “Say if it hurts. My daughters often say I don’t know my own strength.”

“I wish it would… I told you, I feel nothing…”.

I looked at her carefully. She had turned her head away and was gazing straight ahead. It wasn’t possible to not feel the pain of such an injury. I became worried. Perhaps a nerve was damaged by the blow and all sensation lost in the arm. I applied a bit more pressure as I massaged her arm. “Are you sure it doesn’t hurt?” She shifted slightly in her seat and looked me straight in the eye. I am not much given to imagination but I couldn’t decipher that look, I who have raised two daughters and taught numerous girls and know without a second glance when a girl is lying about her periods to get out of a fitness class. All I can say is that I felt that look upon me like a hot ray. It wasn’t an angry glance; intense, yes, but not angry; more searching than penetrating. With a quick movement she placed her left hand on top of my hand as I massaged her arm and pressed hard. I tried to snatch my hand away but she wouldn’t let go. My fingers cracked with the pressure of her palm, my rings bit into my hand. When she released my hand, I was troubled to see the marks of my fingers, indentations from my rings on her bruised, swollen flesh. What was she trying to do? Cause trouble? Angle for money? Surely other passengers must have seen that it was an accident, that I hadn’t hit her deliberately.

“Don’t worry,” she repeated, “it is not your fault. I don’t feel anything anyway. “

The plane had begun taxiing down the runway. I could see her lips moving, shaping unheard words. “I can’t hear you,” I mouthed pointing to my ear. She reached out and took my hand, I can’t feel, she mouthed back.

We sat still as the plane took off. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. “What do you mean?” I asked as soon as the sound of the engines subsided. “Is it a medical condition?”

“I don’t know,” she said slowly, “all I know is that I can’t feel anything. Anything at all. Look,” she turned the inside of her left arm towards me. There were large blisters just below the wrist. “I only realised my wrist was burnt when I was taking off the bangles before my bath.”

I was shocked. “But this is not normal, you must see a doctor.”

She smiled slightly. It was the kind of smile you substitute for tears so as to not make others uncomfortable. I smile it too when people ask me about my father’s sudden death. I absently noted that there was space between her front teeth and that it did not diminish the beauty of her smile. “Yes it is not normal, I do realise that. But doctors can’t do anything about it. I haven’t spoken about my problem much but if you would care to hear, I would like to tell you.”

You see, the thing which troubled her was not my skin but the consequences of having such a skin. If she could just manage to keep me blemish-free till a suitable match was found, everything would be fine. I was married not long after.

“Do tell me. My daughters are only a little younger than you and they have had their share of skin problems. I have a very good home-made ointment of rarified butter made with cow’s milk and nutmeg which cures almost all.” Her eyes remained fixed straight ahead, ” I am afraid it may not be that simple.” She said.

I always had an over-sensitive skin, she began. I bruised easily, causing my mother much worry. Fortunately, I healed quickly too and even the nastiest of bruises would disappear within a short time. When I crossed twenty years without any permanently disfiguring scars, my mother was somewhat relieved. Soon I could be married and after that my sensitive skin would no longer be her problem. You see, the thing which troubled her was not my skin but the consequences of having such a skin. If she could just manage to keep me blemish-free till a suitable match was found, everything would be fine. I was married not long after. I had known my husband and his family, they were our next door neighbours for as long as I could remember. I had played with him and his brothers and sisters as I was growing up. Sometimes his mother or mine would make a joke about our being married and every one would laugh. It was the kind of tedious joke adults make about their kids. Sorry, I am digressing, she apologised, this of course has nothing to do with my problem. That began a few years after my marriage.

I felt nothing in me belonged to me any more … You know the awfulness of crying in snatches so no one knows that you are crying? You never shed enough tears and the misery just settles inside you… perhaps I am not making any sense?

After I got married, I moved next door to my husband’s home. My days were usually spent in housework and looking after my husband’s family. I had to unlearn all the rituals of my parents’ home and learn those of my husband’s. Occasionally, my husband would take me out to watch a movie or to visit his friends. Not too long after my marriage I had my daughter. Everyone was pleased, she was so fair-skinned and beautiful, but of course the family wanted a boy too. My husband too felt it would complete the family. You understand, don’t you?

Of course I understood. My husband and I had tried for a third one for just the same reason. It isn’t that we love our daughters any less, they are very responsible girls and outstanding at studies, but it is good to have a son to repay the debt of ancestors and carry the family name. “Nothing wrong with that,” I said.

Yes, she agreed. By the time my daughter turned three, everyone was reminding me that I must hurry and try for another baby. Increase the family, you won’t be young forever, they’d say. To tell you the truth, it had been tough for me with my daughter. I had been torn badly and the hematoma in my vagina had taken months to resolve. And then the endless nursing … I felt nothing in me belonged to me any more … You know the awfulness of crying in snatches so no one knows that you are crying? You never shed enough tears and the misery just settles inside you… perhaps I am not making any sense?

Tears pricked my eyes. You are, daughter.

One afternoon I was preparing lunch as usual. I’ve never enjoyed cooking much and what I’d have really liked to do that afternoon was to loosen my hair and step out into the sun-filled courtyard.

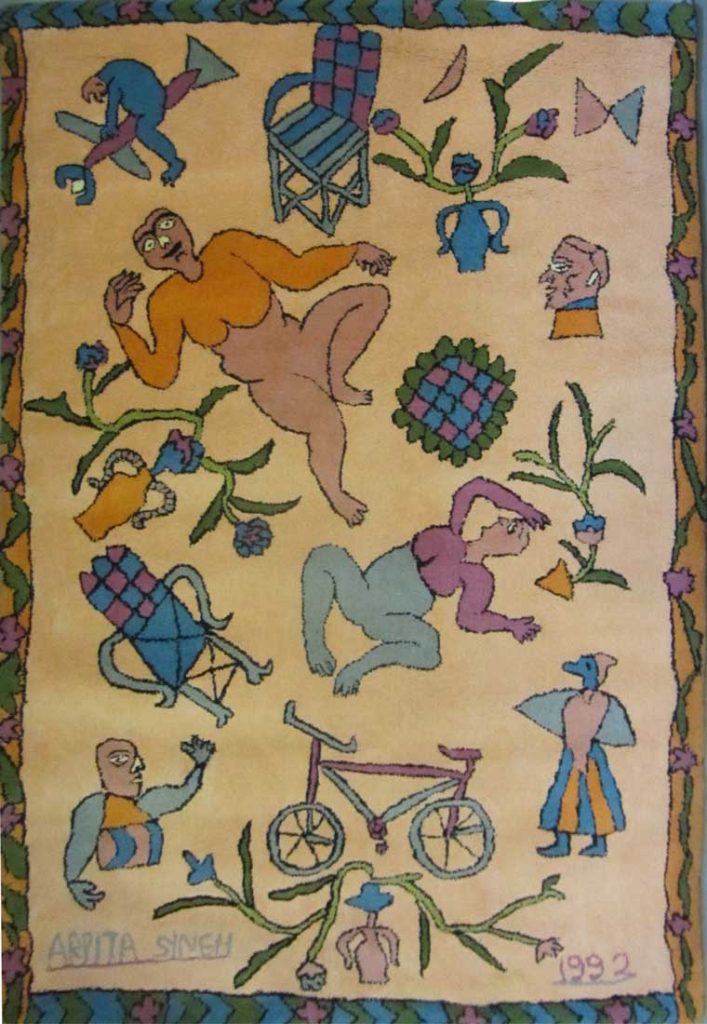

Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation Web

Well, I said, some things are necessary, if you as the daughter-in-law didn’t cook for the family, who would? I used to wake up at 5 in the morning to cook breakfast and lunch for the household before leaving for work and this when my first two were both under five, the second one still nursing at my breast. When I look back, I wonder how I did all that.

How? She asked.

This is not about me, sweet daughter, I replied.

As you wish, she said and continued, that afternoon I was frying gourd for a side-dish. I was sliding thin slices of gourd into the pan when suddenly the oil sizzled and burning specks of it flew about. I was surprised. I could see no reason for the oil to crackle like that. It was then I noticed that there was a deep cut on my index finger and blood was dripping from it into the pan. I was taken aback. I must have cut my finger while slicing the gourd and yet I hadn’t felt any pain. However I had no time to think, my father-in-law is particular about the lunch being served on time. So I sucked my finger and got on with preparing lunch.

I didn’t give this incident much thought till one night a few weeks later when my husband reached for me in bed. My daughter slept on a small cot beside our bed and we had to be careful not to disturb her. Not that there was anything much to it, you know. What’s new after five years of marriage? I knew what he wanted when he circled my body with his arms, cup my breasts and pulled my nightgown all the way up to my neck. Am I making you uncomfortable, she asked?

I shook my head. The description she had given, it could have been my husband and I. I glanced at her face, her brooding eyes, her mouth swollen with unspoken words. You must say what you need to, daughter, I have been a woman much before you, nothing shocks me.

I tried to follow her advice and not think about my problem. But it is difficult to not think about something when you are reminded of it in a hundred different ways. I could no longer feel the soft silk or cotton of my sarees on my skin or the luxurious feel of sesame oil when my mother-in-law’s masseuse gave me a massage. I had to be careful not to scald myself while bathing as I could no longer tell the temperature of the water.

Thank you, she said gratefully. That night he asked if I was still taking my pills. Don’t take them anymore, he told me. After he finished and fell asleep, I went to the bathroom. In the mirror I saw that there marks of his teeth on my neck but I had felt nothing… The next time he held me, I paid attention. That’s when I realised I could not feel his hands on my body or his mouth. I opened my eyes wide and in the mild darkness could make out he was moving inside me. But I felt nothing…

Now I was worried. It was one thing not to feel an occasional cut or bruise and quite another to not be able to feel my own husband. I thought it over for a few days and decided to ask my mother. She might know something about me that I didn’t. Though my parents lived next door and I did not need a formal invitation to visit them, you’d understand that I couldn’t just go to their home whenever I pleased. I had to wait for a suitable opportunity.

Of course, I said, it wouldn’t have been appropriate. No one would countenance their daughter-in-law popping over to her parents’ home all the time. It is your duty to strike the right balance. After all you now belong to your husband’s family.

She lowered her eyes and continued. As it happened, around this time God blessed my brother with a son after many years. My parents selected an auspicious day for feeding the baby his first morsel of rice and milk. Relatives and friends were invited and my mother requested my mother-in-law to send me early that day to help. It was perhaps not the best time to mention my problem to her, the house was milling with guests and my mother was rushed and distracted. But when I found her in the store-room all by herself, setting aside clothes and utensils to give away as gifts to the guests, I could not hold back any longer. Her first thought was that the problem was somehow connected to my delaying having another child. It is not right to meddle with nature, she said, see the troubles your brother’s wife had in conceiving. But my problem is different, far more serious, I can no longer feel my husband’s touch, I told her. She wrinkled her brows, my chattering was causing her to lose count of the gift packets, she complained. Don’t make much of a small matter, she said, after five years of marriage, what do you expect? I didn’t say any more, I was ashamed to bring up my problem when there were so many important things to attend to – the priest had to be given new clothes and grace-money after blessing the baby, the cooks had to be supervised so they don’t skimp on ghee, guests had to be fed, gifts and blessing-money given to the baby had to be set down in the household register my mother maintained.

The doctor examined me hurriedly, wrote a brief prescription and rang for the next patient. I was astonished. He hadn’t asked me anything, hadn’t spoken a word in fact beyond asking me to turn this way or that.

I tried to follow her advice and not think about my problem. But it is difficult to not think about something when you are reminded of it in a hundred different ways. I could no longer feel the soft silk or cotton of my sarees on my skin or the luxurious feel of sesame oil when my mother-in-law’s masseuse gave me a massage. I had to be careful not to scald myself while bathing as I could no longer tell the temperature of the water. I had to be extra watchful of louts when I went shopping. They were a regular nuisance in our city and grabbed at women brazenly. My sisters-in-law complained to my husband that I never objected, never slapped them away. What could I say in response? I couldn’t feel their hands any more than my own husband’s… I was constantly on the edge, exhausted, always watchful …

My problem worsened, I could no longer feel my daughter’s dimpled body in my arms or hands placed on my head in blessing. I decided to speak to my husband. I didn’t quite know how to explain my problem to him so I just said I had a skin problem. He knew all about my sensitive skin of course. I thought your skin was getting better, he smiled meaningfully, you no longer cry out at a little roughness. But I was suffering and insisted on seeing the doctor. The doctor had known me since I was a child. He examined me carefully. There is nothing wrong with your skin, he told me, in fact it is wonderfully elastic and clear, perhaps you should use a little sunscreen, that’s all. I told him a part of my problem – how I would cut my finger and not feel the pain or not feel scalding hot water. He laughed. Good, he said, all that excessive sensitivity caused too much trouble, you should be happy that your skin has become stronger, more tolerant. But he was a kind man and saw that I was troubled, so he referred me to a Neurologist.

My younger sister-in-law had accompanied me to the big hospital where the Neurologist consulted. He was very famous and as we waited to see him, I thought carefully about phrasing my complaint. You see, I did not want to alarm my sister-in-law. The doctor examined me hurriedly, wrote a brief prescription and rang for the next patient. I was astonished. He hadn’t asked me anything, hadn’t spoken a word in fact beyond asking me to turn this way or that. So I asked him what was wrong with me. Nothing at all, he answered, you have sound bones, good reflexes, no weakness of any sort. Just take some calcium and vitamin D and you will feel fine. I couldn’t understand how that was possible. How could there be nothing wrong with me, I asked him? I can’t feel my child nor my husband’s touch, and you say there is nothing wrong with me? The doctor drew together his eyebrows and looked carefully at me. What do you mean, he asked, there is absolutely nothing wrong with your nervous system. Everything is fine. Then why am I not able to feel anything? Why are cold and hot mere words to me now? Why can’t I tell the texture of the grinding stone or my kanjivaram saree apart? I think my voice must have risen because the doctor looked startled and my young sister-in-law turned pale. I knew I was behaving inappropriately, I never meant to say all this, particularly not before my young sister-in-law, not married yet and prone to fainting when agitated but the strain of many months of worry had suddenly overwhelmed me. Do you understand?

I nodded.

The doctor told me to sit down. I hadn’t realised that I had risen from the chair. I returned to the patient’s chair and apologised to him. I am a bit overwrought right now, I said to him, but the fact of the matter is I long to feel my daughter’s soft hair again. The doctor nodded. I think this problem of yours needs to be examined further. I will give you a reference for my colleague. He is in the psychiatry department, an excellent diagnostician when it comes to problems of this nature. I would like him to examine you. He scribbled a brief note and handed it to me. I paid his fee and we left his consultation room. My young sister-in-law was still pale like turmeric, so I took her to the hospital canteen and bought her a cup of hot, sweet tea flavoured with cardamom and some bread and butter. Her colour returned as she ate. I did not want her to tell the family about my outburst so I tried to reassure her. I told her the heat in the closed room must have affected me and that she should not worry my mother-in-law by telling her about my problem. Also I had no faith in the doctor’s suggestion to see a psychiatrist. My problem was purely physical. I mean what could be more physical than the sense of touch?

At night when my husband turned to me, I pretended and imagined. My memory of that period in my life is clouded with the exhaustion of incessantly watching myself, to not give away that I felt nothing.

Of course my young sister-in-law didn’t keep quiet about the incident in the doctor’s room. On hearing her report, my mother-in-law became uneasy. She didn’t say anything to me but called on my mother and discussed the matter with her. I only learnt about their conversation a few days later when my mother asked me over one afternoon. She wanted to get a new set of clothes made for my daughter for an upcoming festival and needed to measure her. My mother was planning an elaborate outfit and I helped her tuck a length of bright yellow silk around my daughter’s small, plump body. Suddenly she exclaimed – you’ve jabbed your finger with the pin, suck it before the blood drips on the silk. I was not sure which finger she meant and had to look at my hands. As I sucked the bleeding finger, my mother looked at me closely. You did not feel the prick, my Pearl, she asked. She hadn’t addressed me by that old endearment for years. What could I say? Hadn’t I told her many months ago and she had told me not to make much of it? My tears fell on the silk in which my daughter was now squirming. My mother sat her down on the floor and gave her some sweets to keep her quiet. She then put her arm around me. You saw the doctor, didn’t you, she said, and the doctor found nothing wrong. I was astounded. How is there nothing wrong, Amma, I asked her, you saw for yourself just now, I couldn’t feel the pin-prick and I can’t feel anything else either. If you can’t feel, then make an effort and imagine, pretend, that’s the only cure she said. Don’t let a small thing like not being able to feel ruin your life. Your mother-in-law is worried. She was talking about consulting a brain-doctor. Reassure her. About what, I asked? About you, foolish girl, tell her you are feeling fine, there’s nothing wrong with you. Take care of your family-life, Pearl. I was bewildered. I was suffering and yet I was to comfort others. So what’s new about that, my mother retorted, that’s what we are supposed to do. She handed me the customary box of sweets, I couldn’t return to my husband’s home empty-handed.

Again, I tried to follow my mother’s advice. I cooked elaborate meals for the family, observed all festivals, kept fasts, looked after my daughter. At night when my husband turned to me, I pretended and imagined. My memory of that period in my life is clouded with the exhaustion of incessantly watching myself, to not give away that I felt nothing. I remember slapping my daughter once when she bit another child and watch the marks of my fingers appear on her soft cheek though I had felt no contact. I also remember allowing a cousin of my husband to kiss me one night in the dark kitchen when the household slept; such was my desperation to feel something, anything.

Then one day I discovered I was pregnant. My husband, his family, my mother, everyone was happy. But as my pregnancy progressed, my dread increased.

Of course, I said, it is normal to be afraid, the pain of child-birth, I can still recall it after all these years.

She looked at me. Don’t you see? I was not afraid of feeling the pain, I was afraid of not feeling it. What if the loss of sensation had penetrated deep into my body, into my womb? What if my muscles and tissues had forgotten the contractions and expansions of life?

As it turned out, she continued, that one was a futile worry. When I was in the eighth month, I slipped on the steps of the temple and landed on my swollen belly. I was rushed to the hospital, my belly was cut open and the baby, a healthy boy, taken from my womb. When I regained consciousness, I saw my perfectly formed baby, a tiny version of my husband, lying beside me. After the baby’s birth I went to stay at my parents’ home. My mother insisted that I recuperate there in keeping with tradition. My daughter-in-law is able to run the household, she told my mother-in-law, and I can give all my attention to my pearl. And she did. She fed me the ritual preparations of herbs and rarified butter, dry fruits and resin to nourish my body. She called the masseuse to massage me every day and my body, slack after the birth, began regaining its elasticity. She made me bathe with milk and turmeric and rose essence and my skin glowed. Once the cut on my belly healed, she bound my belly with lengths of cotton to make it flat again. She also took care of the baby, massaging and bathing him, singing to him and feeding him saffron mixed in my breast milk. At night too she would take him away after I nursed him so I could sleep. Everyone who saw me commented on how beautiful I looked, my body filled out, my eyes bright and clear. Though my problem was not cured, at my parent’s home there was no need to be watchful all the time. For the first time in almost two years, I relaxed.

The evening before I was to return to my husband’s home, my mother came to me. She undid my long braid and began massaging my scalp with fragrant oil. Are you well, my Pearl? Yes, Amma, I replied, for what else could I say after the care she had taken of me? She was pleased with my answer. You see I was right, she said, all that not being able to feel was nonsense. Now you have a son, you look even more desirable than on your wedding day and your husband and his family are very happy. You just make sure you focus on these things, they are the ones that matter. Forget everything else. The next morning my husband came and fetched me back to his home.

I was not afraid of feeling the pain, I was afraid of not feeling it. What if the loss of sensation had penetrated deep into my body, into my womb? What if my muscles and tissues had forgotten the contractions and expansions of life?

At my husband’s home things slid into a new pattern. I would be up half the night nursing my son. My daughter, jealous of the new baby, wanted me all the time too. My days were filled with household tasks and at night, my bed crowded with the children, my problem exacerbated. I couldn’t feel my own self. I constantly had little accidents, cutting or burning myself. However my biggest anxiety was about nursing my son. My breasts would be stone-hard, engorged with milk and I wouldn’t realise. Often I would press my breast into my son’s tiny mouth and see it slipping desperately against the hardness.

The front of her blouse was damp and a milky smell rose from her. I nodded in sympathy. I knew what a nuisance that could be. Where is your baby, daughter? You need to nurse him soon. Would he be at the airport when we reach Kashi, I asked?

My baby? She turned away from me. I don’t know where he is.

I was astonished. What do you mean? He is still nursing, how can you not know where he is?

She smoothed the free end of her saree to cover her taut, leaking breasts. Three nights ago, my son woke up in the middle of the night, she said. I was too tired to get up so I turned over on my side and gave him my engorged breast. I fell into a daze as he tried to suck and release the pent-up milk. When I awoke, his little face was pressed under my breast and he was not breathing…

Oh you unhappiest of women… My eyes filled with tears.

She regarded me with wide, dry eyes. My husband said he couldn’t trust me with our daughter. His family didn’t want me in their home any longer. Neither did my parents. So I am going to Kashi. It belongs to the God who chose everything that others shun, everything poisonous and repellent and unclean. I shall live in his city now.

So I am going to Kashi. It belongs to the God who chose everything that others shun, everything poisonous and repellent and unclean. I shall live in his city now.

Anukrti Upadhyay writes fiction and poetry in both English and Hindi. Her Hindi works include a collection of short stories titled Japani Sarai (2019) and the novel Neena Aunty (2021). Among her English works are the twin novellas, Daura and Bhaunri (2019), and her novel Kintsugi (2020); the latter won her the prestigious Sushila Devi Award 2021 for the best work of fiction written by a woman author. Her writings have also appeared in numerous literary journals such as The Bombay Review, The Bangalore Review and The Bilingual Window. Anukrti has post-graduate degrees in management and literature, and a graduate degree in law. She has previously worked for the global investment banks, Goldman Sachs and UBS, in Hong Kong and India, and currently works with Wildlife Conservation Trust, a conservation think tank. She divides her time between Mumbai and the rest of the world, and when not counting trees and birds, she can be found ingratiating herself with every cat and dog in the vicinity.