Discourse :: Ratna Raman

I was rather young enough when I first heard of Shabari. My grandparents presented us with variations from Valmiki’s two-thousand-year-old narration (Sarga 69 of the Aranyakanda) as well as one from the eight-hundred-year-old Kamban Ramayanam written in Tamil. Their version was about an elderly woman, a disciple of Rishi Matanga. When informed by Matanga that it was time for him to leave behind his mortal frame, Shabari had wanted to follow suit. Dissuading her, Matanga instructed her to await Vishnu’s visit in human form and extend hospitality to Rama before embarking on her final journey. Shabari was a kindhearted and affectionate host who fed Rama and Lakshmana and then voluntarily entered fire, relinquishing life in the world.

Shabari’s life in the idyllic landscape of Lake Pampa, beside the Rishyamukha Mountain, was fascinating. The sand around the lake was soft and easy to walk upon, making it pleasurable for human feet. Abundant fruit, fish, and boar provided for varied appetites to feed upon. Lotuses and water lilies bloomed in profusion and several kinds of birds nestled on trees and grasses nearby.

Possibly this was somewhere near modern-day Hampi, which still remains scenic and salubrious, despite continued human depredations. The weather was delightful all year round, even in the days of yore, and Shabari always recalled for me the grandmothers we stayed with in Madras and Chidambaram in the long summer vacations when we escaped from brutal Delhi summers and the monotonous everyday schedules of school.

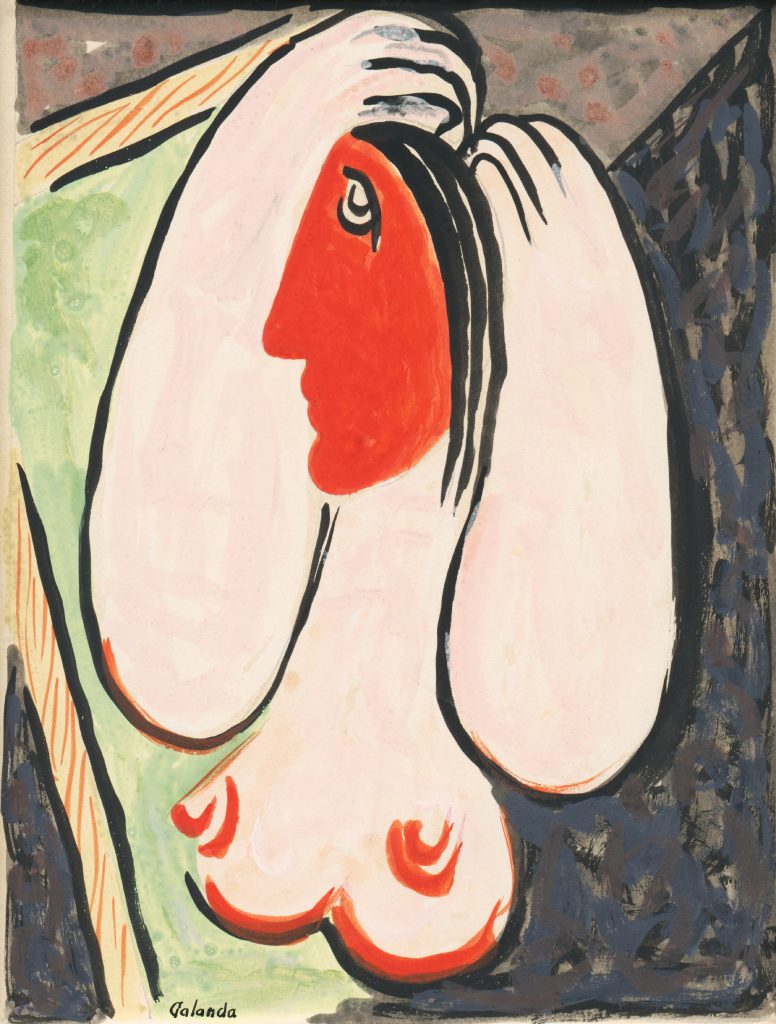

Original from the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Having raised their children to adulthood, my grandmothers were probably steeped in the bhakti tradition that translated into the devoted attention they extended in everyday life to all their near and dear ones. I am sure that for them, in the mellow autumn of their lives, Shabari was a significant point of reference.

Shabari had made the ashram a welcoming place and the warmth and generosity extended to her visitors knew no bounds. Modelling themselves on Shabari, my grandmothers became extraordinary reservoirs of nurture and warmth, as they bustled around visiting families, making them feel welcome. rustling up all manner of delicious fruits, growing in and around their homes, going to great trouble to assemble delicious meals for large families. The first sip of coconut water, or bite of green mangoes in raw and pickled avatars

and then the divinely sweet fruit itself were memories introduced by my grandmothers who were indulgent hostesses, nonpareil.

I remember finding a fully ripe wood-apple and taking it to my grandmother one summer. She cracked the fruit with an olakkai (iron mortar) scooped it out, crumbled jaggery over the pulp and garnished it with cardamom. We both polished off that wood-apple together and to date, it remains a memory of a texture and flavour that has never been replicated.

Growing a little older, I learnt that Sabara was a noun that described a socially disadvantaged community to which Shabari belonged, quite unlike the Rishis and Kshatriya princes she served with selfless

devotion. Five hundred years ago, in the Adhyatma Ramayana, Shabari speaks of her spiritual unworthiness due to her low status and awaits Rama’s reassurance of its irrelevance before immolating herself to attain liberation. The Adhyatma Ramayana records the increasing rigidity of caste hierarchies while confirming the lowly status of women in the patriarchal hierarchy. By this time, the considerate and compassionate Shabari, became for me the lode – stone of integral human values such as selfless nurture and unconditional love, that were increasingly being jettisoned.

My mother explained how the ‘ecchal’ ber (jujubes touched by human saliva) accepted by Rama and consumed joyously not only repudiated caste hierarchies but that Sabari’s gesture broke with antediluvian practices giving her an iconic status uptil the pre-Covid era. It is fifteenth-century poet Balram Das’s more recent Dandi Ramayana (Odiya) that first identifies the jhoota (saliva-touched) fruit as mangoes. Arguably, the version of the saliva-flecked ber exists as an oral narrative all over the Indian subcontinent and provides great direction. The ‘touch-ability’ and ‘taste-ability’ that Shabari invokes through biting into each individual fruit is an extraordinary metaphor reminding us of the urgent human imperative to transform and transcend hateful structures of class, caste, gender, and race to allow humanity to arrive at a more egalitarian space.

An undocumented tale mentions the wealthy tribe Sabari had fled from in the days prior to her marriage, aghast at the wasteful culling of animals for the wedding feast, to seek refuge at Matanga’s ashram. The idea of a younger Shabari who rejected conjugality as defining or completing female identity continues to rivet. Here we have an outright rejection of heteronormativity from a long time ago that has never been under discussion. This young version of Sabari who chose to pursue her heart’s desire continues to remain little known and less validated. The Shabari we are familiar with is the kind and hospitable elderly woman who waited upon Rama and Lakshmana with her jhootey ber.

What of the Shabari who followed her heart’s desire and would make for a significant female role model? A Shabari whose intellectual and spiritual prowess outranked or was on par with patriarchal men contributing to sustainable living and careful about what she consumed; she remained courteous and hospitable while standing her own ground, in the face of great odds.

It is unlikely that she was not victimised in those spectacular ancient environs: for her free-thinking, for her youth, for her lower social status, for being a woman, for wanting to be different: Shabari must have been made to suffer. Incongruously, Sabarimalai or Shabari’s mountain in the twenty-first century has been a pilgrim site for men of all ages but remains out of bounds for women between the ages of ten and fifty. Women activists who tried to change this situation were made to cower in the face of opposition from the state and conservative families. In myth as in life, Shabari’s real options seem to have dwindled.

Oddly, although posterity has chosen to enshrine only the self-effacing old woman and has shut down discussions on the subject of women’s access to spirituality or their repudiation of sexual desire, I have longed to meet this free-spirited young woman who valued goodwill and nurture as intrinsic and extended largesse to all sentient beings, while displaying extraordinary qualities of grace and dignity under pressure. Although I have never run into Rama, it is the countless articulate Shabaris around us; old, middle-aged, and young, that I continue to seek. May their tribe increase.

Dr. Ratna Raman is a professor of English literature at Sri Venkateswara College, Delhi University. Specializing in Feminism, Women’s writing, Nineteenth-century literature, Modern Poetry and the Novel, Classical Indian Literature, she is also the author of ‘The Fiction of Doris Lessing’ (2021, Bloomsbury).