A

VINDICATION OF THE MONSTROUS MYSTIQUE : THE TROUBLE WITH PROCREATION, AND

FEMINIST JURISPRUDENCE IN AGAMEMNON

“A

shudder in the loins engenders there

The

broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And

Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So

mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she

put on his knowledge with his power …?”

–

Leda and the Swan, W.B.Yeats

“We must kill the false woman who is preventing the live one

from breathing”

–

The Laugh of the Medusa, Helene Cixous

Aeschylus’ Agamemnon

(5th Century B.C.), part of the Oresteia (Ὀρέστεια) trilogy, is augmented as a historical artifact

that is domineered by legal imagery. Its mythopoesis is hegemonized by the

Trojan War, riding roughshod over the theft of Helen and ending with the

adversarial counter-prosecution by Athena, under the supervision of Zeus. The

homicidal audacities in the narrative are not coincidentia oppositorum but, contrastingly, they confront combats

: of Olympian over chthonic (Divinity), Greek over Barbarian (Culture), and

male over female (Society). Antiquarian women have perforce been leading at the

helm of Western liberalization, with Latinate samaritans like Camilla,

Semiramis, Artemisia and Cleopatra directing their motherlands to warfare.

Aiming to juxtapose such a monstrous androgyne with the myth of matriarchy,

Orestes assassinates his mother, the deceptive and tragic wife Clytemnestra, in

open alliance with Apollo.

Agamemnon

Clytemnestra, Twilight of the Matriarch

J J Bafochen asserts in ‘Mutterrecht

und urreligion’ (1967) that Greek heroes like Herakles and Theseus laid

their crusades foremost against the feminine Amazonomachy figures, who were

deemed to be feminine (earthborn) beasts. Joan Bamberger elaborates on this

hypothesis, proclaiming that female sexual dimorphism (unbridled sexual

transgressions) acted as a social charter for ‘chaos and misrule’. Since

Clytemnestra performs the gynocratic slaughter as a domestic vendetta (ruling

on behalf of husband-monarch), her act is equated to the Danaids who slay their grooms on the wedding night. At the same

time, her adulterous lover Aegisthus vociferates as the powerless lion and the

chorus calls him an ‘effeminate woman’.

He is ironically destined to a similar fate as that of Agamemnon who confessed

to his sensual weakness for Cassandra, the concubine from Troy. In a reversal

of roles, reminiscent of Hercules’ enslavement to Queen Omphale, the Rule of Women pioneers as a political

issue here, in a misogynistic progression from Althaea (mother) & Scylla

(daughter) to Clytemnestra (Wife).

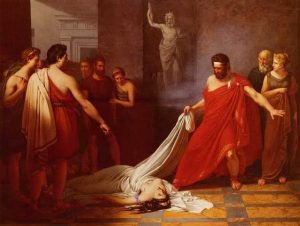

Pierre-Narcisse Guérin. Clytemnestra

hesitating before stabbing Agamemnon, 1817. Louvre, Paris.

Clytemnestra kills Cassandra

Outraged by the abhorrent extermination of her daughter

Iphigenia, the female havoc ripples shockwaves on Argos and subsequently to the

Universe. Furies, the schizophrenic

products of Clytemnestra’s vengeful dreams, and the virginal Erinyes, transmutations of her blood

guilt – all act in cognizance as Daughters of the Night, delegating as paides apaides (‘children who are not

children’). Her negative sexuality

marshals towards a primordial malevolence, hysterically attempting to liquidate

even her own son in the guise of the Serpent:

Who is so childish or bereft of

sense as to get his heart

excited by the sudden news of the

beacon

…It’s just like a woman to believe a

thing before it is clear (479-84)

The Remorse of Orestes (1862). W-A. Bougereau.

Bamberger shows that puberty

initiation rites detach the pubescents from the care of natal maternity and

regroups them with mature males, usurping women’s sovereign rights. For

Orestes, his peripheral exile during childhood and fortuitous return during

puberty – both are undertaken as consequences of maternal savagery. Moreover,

his revenge as the lawful successor to the throne inevitably causes a

separation from his mother, who is first tried as a wife (“For it is not the same thing that a noble man die, with

God-given sovereignty, at the hands of a woman at that”) and then as a Mother, the archetype of vindictive frisson. Be that as it may,

‘a state cannot be changed without first being annihilated’ (Eliade 1958). In

the play, the succession myth is situated alongside the ‘final oracular

beginning’, i.e., destruction is transformed into creation by the female, in

order to attain peace.

Philippe Auguste Hennequin, 1762-1833

The Erinyes’ impulse to guzzle, engulf and paralyze Orestes

in the darkness of Hades is a transpersonalized endeavor at female retaliation.

As the dragon of retributive justice cannot be slain, it must be tamed.

Pertaining to a pacifying reprisal in the drama, the demonic performativity

accentuates a pathway for a socio-collective, non-violent, persuasive trial (Peitho). Contrary to Aristophanes’s Thesmophoriazusae, where the female is

nude (pornographic) and mute, Clytemnestra refuses staticity and demands divine intervention from

Zeus, Ate and the daimon. A

heterogenetic spectator is aware that she inclines towards criminality only as

a susceptible defense against mutual

recriminations.

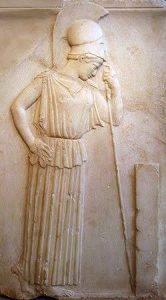

The pensive Athena

Her ordinance (horos)

and political gallantry (krotos) is

announced by a masculine (provocative) crudity of language. Helen P. Folly

argues that her ontological lack of shame preserves the fires of Troy’s

demolition and frames the battalion metaphorically within the house of Atreus.

Owing to her speech-act, she exhibits a bravura that unapologetically reveals

the predicament of the defeated survivors (Gagarin 1976). For her, the ostracized gender must speak for

the afflicted. Indeed, she is bound to adopt a male rhetoric (bilingual paradoxes),

commit to scandalizing honesty and overthrow deferential gnomes, yet, as

Goldhill argues, ‘her weapon is a net, not a sword’.

Rape of Cassandra, the Prophetess

Like Eumenides,

conjugality (patriarchal unions) rigorously subverts biophysiological roles,

inasmuch as Athena was born from Zeus’ head. Concurrently, Aristotle

demonstrates that even though the fecund body (soma) withholds the pneuma

(divine seminal fluid), its soul and essence (ousia) are produced from the male

brain. Therefore, advancing the myth of virginal maternity, the Apollonic

theogony also appropriates female embryology, eradicating the last identity

that she could call her own.

Orestes slaying Aegisthus and Clytemnestra

2nd Century AD, State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Conclusively, it is intuitive on the part of Clytemnestra

that she considers Cassandra to be her own alter-ego, attributing her active

sexuality onto her insane prophecy.

Within the paraphernalia of double standards, her epistemological integrity can

be perceived as monstrous to the orthodox Elders, for she repudiates the way

they call Helen a man-destroyer. She also reformulates the inheritance law,

placing her daughter into direct lineage, while the Furies prevent Orestes from

ascending. Nevertheless, the animosity towards female terror, and its

absolutist affirmation is the proof that Greek tragedies were insubordinately

modern for its time and the female signification of the polis was refurbished with each instance of monstrous valor.

Works Cited:

Aeschylus. Oresteia:

Agamemnon. University of California Press, 2014.

Creed, Barbara. The

Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. Routledge, Taylor &

Francis Group, 2015.

DesBouvrie, Synnøve. Women

in Greek Tragedy: An Anthropological Approach. Norwegian Univ. Press, 1992.

Foley, Helene P. Female

Acts in Greek Tragedy Female Acts in Greek Tragedy. Princeton University

Press, 2009.

McClure, Laura. Spoken

like a Woman: Speech and Gender in Athenian Drama. Princeton Univ. Press,

2010.